Linux IPC with Pipes

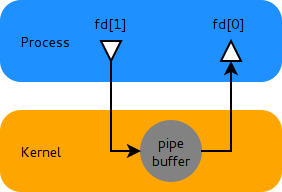

27 Jul 2012Inter-Process Communication (IPC) is a set of methods for exchanging data among multiple processes. IPC is a very common mechanism in Linux and Pipe maybe one of the most widely used IPC methods. When you type cat foo | grep bar, you create a pipe to connect stdout of cat to stdin of grep. A pipe, as its name states, can be understood as a channel with two ends. Pipe is actually implemented using a piece of kernel memory. The system call pipe always create a pipe and two associated file descriptions, fd[0] for reading from the pipe and fd[1] for writing to the pipe.

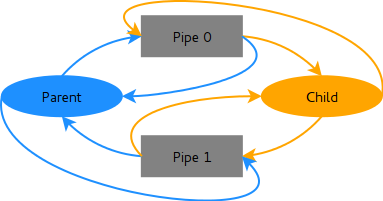

Pipe is always used with fork, because using pipe within one process is meaningless. In the example, two pipes are created.

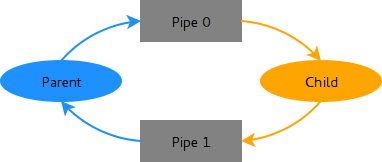

After pipe and fork, both parent process and child process can read and write to both pipes. However, a pipe is unidirectional. If the parent process write the pipe1 and then read from pipe1, it will get the same data written before. And that’s why two pipes are created, pipe1 for data flow from parent to child and pipe2 for data flow from child to parent. Unneeded pipe descriptions must be closed.

After that, we use dup2 to connect stdin of the child to pipe1 and stdout of the child to pipe2. The pipes are transparent for the child process, it has no idea that it’s reading from a pipe and writing to another pipe. Then the parent process can use the two pipes to communicate with the child. In the example program, the child process executes rev, which reverse each line it reads from stdin and print the result to stdout. The parent process passed everything it reads from stdin to the child and redirects everything the child prints to stdout.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/wait.h>

int main()

{

// from parent to child, parent write, child read

int pp2c[2];

// from child to parent, child write, parent read

int pc2p[2];

pipe(pp2c);

pipe(pc2p);

switch (fork()) {

// fork failed

case -1:

break;

// child

case 0:

// connect pp2c to stdin

close(pp2c[1]);

dup2(pp2c[0], STDIN_FILENO);

close(pp2c[0]);

// connect pc2p to stdout

close(pc2p[0]);

dup2(pc2p[1], STDOUT_FILENO);

close(pc2p[1]);

// exec "rev" to reverse lines

execlp("rev", "rev", (char*) NULL);

// exit with code 127 if exec fails

perror("exec failed");

exit(127);

break;

// parent

default:

// close unecessary pipes

close(pp2c[0]);

close(pc2p[1]);

// open pipes as stream

FILE *out = fdopen(pp2c[1], "w");

FILE *in = fdopen(pc2p[0], "r");

char word[1024];

// redirect input to child process

while (scanf("%s", word) != EOF) {

fprintf(out, "%s\n", word);

}

fclose(out);

// read child process output

while (fscanf(in, "%s", word) != EOF) {

printf("%s\n", word);

}

fclose(in);

// call wait on exited child

wait(NULL);

break;

}

return 0;

}The suitable situation to use pipe is IPC among related processes (related by fork) and the communication should be simple enough to use raw binary bytes. The perfect and classic application of pipe is executing binary programs, which is the scenario behind almost every command line typed in a shell. The limitation of pipe is also straightforward: only applies to realted processes and only one-to-one communications. For more advanced IPC, consider FIFO, MessageQueue, Shared Memory and Socket.